Jamaica’s Yoruba people

Charting the history of the Yoruba

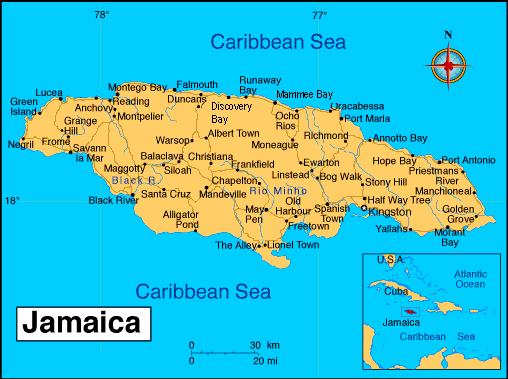

Jamaica, the Caribbean, and Latin America can be described as multi-ethnic and multicultural spaces with various retentions of the original groups of people who first inhabited the areas. Between 1837 and 1867, over 11,000 free Africans arrived in Jamaica to work on sugar estates, while an even larger number worked in other Caribbean and Latin American territories.

Most of these immigrants were from Central Africa, the Yoruba and Dahomy coasts, and the Niger Delta. After their period of servitude, many of the workers returned to Africa, while many settled in Jamaica and other islands such as Cuba, St Lucia, and Trinidad.

A large part of the groups that settled were the Yoruba people who originated

from South West of Nigeria, and the republics of Benin and Togo. These people not only brought tangible skills such as tanning, blacksmithing and agriculture to the Caribbean, they also introduced intangible belief systems and world views in the form of religion or spirituality.

In Jamaica, the Yoruba were responsible for introducing words into the Jamaican vocabulary such as ‘mumu’, which refers to a stupid person, and ‘poto-poto’, which refers to something being muddy. Jamaican writer Olive Senior adds that the original Yoruba people who came to Jamaica also named places such as Naggo Head, Naggo Town, and the village of Abeokuta more commonly known as Bekuta, in Hanover. Abiodun Adetugbo, in his article ‘The Yoruba in Jamaica’, states that Yoruba people also introduced the traditional building method of wattle and daub.

In this building method, stakes are sunk about two feet into the ground and interlocked, horizontally, with twigs and branches and then plastered with mud or clay to form the walls of a house or hut. They also introduced food and plants such as ‘akara’ which is more commonly known as salt fish fritters, and the kola nut, which is more commonly known as bizzy.

Headlines Delivered to Your Inbox

Sign up for The Gleaner’s morning and evening newsletters.

In Jamaica, there are remnants of the spiritual beliefs of the Yoruba people who came to Jamaica. These are found in the practise of Ettu, or Etu, which is an elaborate ceremony performed on commemorative occasions by a community of Yoruba descendants in the parish of Hanover, usually as part of wedding celebrations or as part of ‘nine nights’.

Numbers and colours

In the wider Caribbean and Latin America and the Yoruba system of Spirituality that has survived is the belief in orishas. The orisha tradition originated from the Yoruba people and made up of a pantheon of gods and goddesses, who are said to be the emissaries of Olodumare, or God Almighty, and who rule over the forces of nature and the endeavours of humanity.

Believers say that these god and goddesses recognise themselves and are recognised through their different numbers and colours, and each has their own favourite foods and other things which they like to receive as offerings and gifts. Believers say that when offerings are made in a manner that the gods are accustomed to, the prayers and favours of humans are recognised and they come to our aid.

Today, this belief system still flourishes in many parts of the Americas such as Brazil in the form of Candomble and Macumba, in Cuba as Lucumi or Santeria and Bembe, and in Trinidad and Grenada Shango or Orisha, and in St Lucia as Kele.

Perhaps the most popular of the pantheon of gods to survive in the New World is Shango, also known as Changó or Xangô in Latin America. History says that Shango was the legendary fourth king of the ancient kingdom of Oyo in Nigeria, and that his rule was marked by a whimsical use of power.

One account asserts that Shango was so fascinated with magical powers, that he inadvertently caused a thunderstorm, and lightning struck his own palace, killing many of his wives and children.

In repentance, he left his kingdom and travelled to Koso, where he hung himself. When his enemies cast contempt upon his name, a rash of storms destroyed parts of Oyo.

Shango’s followers proclaimed him a god and said that the storms were Shango’s wrath avenging his enemies. All of the stories concerning Shango involves the theme of capricious, authoritative, creative, destructive, magical, medicinal, and moral power.

As an orisha, Shango is said to love all the pleasures of the world – dance, drumming, women, song, and eating. He is said to rule over lightning, thunder, fire, and drums. He is a warrior orisha with quick wit and a quick temper and is the epitomy of virility. Believers and worshippers of this orisha recognise him through the use of the colours red and white, and through the use of the numbers four and six.

Staffs such as the one pictured are usually commissioned by priests and devotees of Shango and used in ritual dance. They are said to invoke his striking power and protection.

Traditionally these staffs were made out of wood and feature kneeling woman with a double-edged wooden axe on top of her head. In popular Jamaican culture, dancehall and reggae artist Clifton George Bailey more popularly known as Capleton, uses several monikers, two of which are ‘King Shango’ and the ‘Fireman’.

Bailey has gone on record saying that he has rejected the name given to him at birth and prefers to be referred to as King Shango, given its roots in the Yoruba language. Just as the orisha Shango has been described as aggressive, quick-tempered, virile, and a lover of women, we see this persona reflected in the music of Capelton.

Information compiled by Sharifa Balfour, assistant curator, National Museum Jamaica, Institute of Jamaica .